T-test

Overview

T-statistic

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle\hat\beta }[/math] be an estimator of parameter β in some statistical model. Then a t-statistic for this parameter is any quantity of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ t_{\hat{\beta}} = \frac{\hat\beta - \beta_0}{\mathrm{s.e.}(\hat\beta)}, }[/math]

where β0 is a non-random, known constant, and [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle s.e.(\hat\beta) }[/math] is the standard error of the estimator [math]\displaystyle{ \scriptstyle\hat\beta }[/math].

Two sample test assuming equal variance

The t statistic (df = [math]\displaystyle{ n_1 + n_2 - 2 }[/math]) to test whether the means are different can be calculated as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ t = \frac{\bar {X}_1 - \bar{X}_2}{s_{X_1X_2} \cdot \sqrt{\frac{1}{n_1}+\frac{1}{n_2}}} }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ s_{X_1X_2} = \sqrt{\frac{(n_1-1)s_{X_1}^2+(n_2-1)s_{X_2}^2}{n_1+n_2-2}}. }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ s_{X_1X_2} }[/math] is an estimator of the common/pooled standard deviation of the two samples. The square-root of a pooled variance estimator is known as a pooled standard deviation.

- Pooled variance from Wikipedia

- The pooled sample variance is an unbiased estimator of the common variance if Xi and Yi are following the normal distribution.

- (From minitab) The pooled standard deviation is the average spread of all data points about their group mean (not the overall mean). It is a weighted average of each group's standard deviation. The weighting gives larger groups a proportionally greater effect on the overall estimate.

- Type I error rates in two-sample t-test by simulation

Assumptions

The Four Assumptions Made in a T-Test

Two sample test assuming unequal variance

The t statistic (Behrens-Welch test statistic) to test whether the population means are different is calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ t = {\overline{X}_1 - \overline{X}_2 \over s_{\overline{X}_1 - \overline{X}_2}} }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ s_{\overline{X}_1 - \overline{X}_2} = \sqrt{{s_1^2 \over n_1} + {s_2^2 \over n_2}}. }[/math]

Here s2 is the unbiased estimator of the variance of the two samples.

The degrees of freedom is evaluated using the Satterthwaite's approximation

- [math]\displaystyle{ df = { ({s_1^2 \over n_1} + {s_2^2 \over n_2})^2 \over {({s_1^2 \over n_1})^2 \over n_1-1} + {({s_2^2 \over n_2})^2 \over n_2-1} }. }[/math]

See an example The Satterthwaite Approximation: Definition & Example.

Paired test, Wilcoxon signed rank test

- Have you ever asked yourself, "how should I approach the classic pre-post analysis?"

- How to best visualize one-sample test?

- Can R visualize the t.test or other hypothesis test results?, gginference package

- Wilcoxon Test in R

- How Do We Perform a Paired t-Test When We Don’t Know How to Pair? 2022

Z-value/Z-score

If the population parameters are known, then rather than computing the t-statistic, one can compute the z-score.

Nonparametric test: Wilcoxon rank sum test

Mann–Whitney U test/Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test

Sensitive to differences in location

Wilcoxon test in R: how to compare 2 groups under the non-normality assumption using wilcox.test()

Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test and a small sample size. if performing a WMW test comparing S1=(1,2) and S2=(100,300) it wouldn’t differ of comparing S1=(1,2) and S2=(4,5). Therefore when having a small sample size this is a great loss of information.

Nonparametric test: Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

Sensitive to difference in shape and location of the distribution functions of two groups

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic for a given cumulative distribution function F(x) is

- [math]\displaystyle{ D_n= \sup_x |F_n(x)-F(x)| }[/math]

where supx is the supremum of the set of distances.

Gene set enrichment analysis The Enrichment score ES is is the maximum deviation from zero of P(hit)-P(miss). For a randomly distributed S, ES will be relatively small, but if it is concentrated at the top or bottom of the list, or otherwise nonrandomly distributed, then ES(S) will be correspondingly high. When p=0, ES reduces to the standard Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic. c; when p=1, we are weighting the genes in S by their correlation with C normalized by the sum of the correlations over all of the genes in S.

- [math]\displaystyle{ P_{hit}(S, i) = \sum \frac{|r_j|^p}{N_R}, P_{miss}(S, i)= \sum \frac{1}{(N-N_H)} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ N_R = \sum_{g_j \in S} |r_j|^p }[/math].

See also Statistics -> GSEA.

Limma: Empirical Bayes method

- Some Bioconductor packages: limma, RnBeads, IMA, minfi packages.

- The moderated T-statistics used in Limma is defined on Limma's user guide.

- Diagram of usage ?makeContrasts, ?contrasts.fit, ?eBayes

lmFit contrasts.fit eBayes topTable x ------> fit ------------------> fit2 -----> fit2 ---------> ^ ^ | | model.matrix | makeContrasts | class ---------> design ----------> contrasts - Moderated t-test mod.t.test() from MKmisc package

- Examples of contrasts (search contrasts.fit and/or model.matrix from the user guide)

# Ex 1 (Single channel design): design <- model.matrix(~ 0+factor(c(1,1,1,2,2,3,3,3))) # number of samples x number of groups colnames(design) <- c("group1", "group2", "group3") fit <- lmFit(eset, design) contrast.matrix <- makeContrasts(group2-group1, group3-group2, group3-group1, levels=design) # number of groups x number of contrasts fit2 <- contrasts.fit(fit, contrast.matrix) fit2 <- eBayes(fit2) topTable(fit2, coef=1, adjust="BH") topTable(fit2, coef=1, sort = "none", n = Inf, adjust="BH")$adj.P.Val # Ex 2 (Common reference design): targets <- readTargets("runxtargets.txt") design <- modelMatrix(targets, ref="EGFP") contrast.matrix <- makeContrasts(AML1,CBFb,AML1.CBFb,AML1.CBFb-AML1,AML1.CBFb-CBFb, levels=design) fit <- lmFit(MA, design) fit2 <- contrasts.fit(fit, contrasts.matrix) fit2 <- eBayes(fit2) # Ex 3 (Direct two-color design): design <- modelMatrix(targets, ref="CD4") contrast.matrix <- cbind("CD8-CD4"=c(1,0),"DN-CD4"=c(0,1),"CD8-DN"=c(1,-1)) rownames(contrast.matrix) <- colnames(design) fit <- lmFit(eset, design) fit2 <- contrasts.fit(fit, contrast.matrix) # Ex 4 (Single channel + Two groups): fit <- lmFit(eset, design) cont.matrix <- makeContrasts(MUvsWT=MU-WT, levels=design) fit2 <- contrasts.fit(fit, cont.matrix) fit2 <- eBayes(fit2) # Ex 5 (Single channel + Several groups): f <- factor(targets$Target, levels=c("RNA1","RNA2","RNA3")) design <- model.matrix(~0+f) colnames(design) <- c("RNA1","RNA2","RNA3") fit <- lmFit(eset, design) contrast.matrix <- makeContrasts(RNA2-RNA1, RNA3-RNA2, RNA3-RNA1, levels=design) fit2 <- contrasts.fit(fit, contrast.matrix) fit2 <- eBayes(fit2) # Ex 6 (Single channel + Interaction models 2x2 Factorial Designs) : cont.matrix <- makeContrasts( SvsUinWT=WT.S-WT.U, SvsUinMu=Mu.S-Mu.U, Diff=(Mu.S-Mu.U)-(WT.S-WT.U), levels=design) fit2 <- contrasts.fit(fit, cont.matrix) fit2 <- eBayes(fit2) - Example from user guide 17.3 (Mammary progenitor cell populations)

setwd("~/Downloads/IlluminaCaseStudy") url <- c("http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/marray/IlluminaCaseStudy/probe%20profile.txt.gz", "http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/marray/IlluminaCaseStudy/control%20probe%20profile.txt.gz", "http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/marray/IlluminaCaseStudy/Targets.txt") for(i in url) system(paste("wget ", i)) system("gunzip probe%20profile.txt.gz") system("gunzip control%20probe%20profile.txt.gz") source("http://www.bioconductor.org/biocLite.R") biocLite("limma") biocLite("statmod") library(limma) targets <- readTargets() targets x <- read.ilmn(files="probe profile.txt",ctrlfiles="control probe profile.txt", other.columns="Detection") options(digits=3) head(x$E) boxplot(log2(x$E),range=0,ylab="log2 intensity") y <- neqc(x) dim(y) expressed <- rowSums(y$other$Detection < 0.05) >= 3 y <- y[expressed,] dim(y) # 24691 12 plotMDS(y,labels=targets$CellType) ct <- factor(targets$CellType) design <- model.matrix(~0+ct) colnames(design) <- levels(ct) dupcor <- duplicateCorrelation(y,design,block=targets$Donor) # need statmod dupcor$consensus.correlation fit <- lmFit(y, design, block=targets$Donor, correlation=dupcor$consensus.correlation) contrasts <- makeContrasts(ML-MS, LP-MS, ML-LP, levels=design) fit2 <- contrasts.fit(fit, contrasts) fit2 <- eBayes(fit2, trend=TRUE) summary(decideTests(fit2, method="global")) topTable(fit2, coef=1) # Top ten differentially expressed probes between ML and MS # SYMBOL TargetID logFC AveExpr t P.Value adj.P.Val B # ILMN_1766707 IL17B <NA> -4.19 5.94 -29.0 2.51e-12 5.19e-08 18.1 # ILMN_1706051 PLD5 <NA> -4.00 5.67 -27.8 4.20e-12 5.19e-08 17.7 # ... tT <- topTable(fit2, coef=1, number = Inf) dim(tT) # [1] 24691 8 - Three groups comparison (What is the difference of A vs Other AND A vs (B+C)/2?). Contrasts comparing one factor to multiple others

library(limma) set.seed(1234) n <- 100 testexpr <- matrix(rnorm(n * 10, 5, 1), nc= 10) testexpr[, 6:7] <- testexpr[, 6:7] + 7 # mean is 12 design1 <- model.matrix(~ 0 + as.factor(c(rep(1,5),2,2,3,3,3))) design2 <- matrix(c(rep(1,5),rep(0,5),rep(0,5),rep(1,5)),ncol=2) colnames(design1) <- LETTERS[1:3] colnames(design2) <- c("A", "Other") fit1 <- lmFit(testexpr,design1) contrasts.matrix1 <- makeContrasts("AvsOther"=A-(B+C)/2, levels = design1) fit1 <- eBayes(contrasts.fit(fit1,contrasts=contrasts.matrix1)) fit2 <- lmFit(testexpr,design2) contrasts.matrix2 <- makeContrasts("AvsOther"=A-Other, levels = design2) fit2 <- eBayes(contrasts.fit(fit2,contrasts=contrasts.matrix2)) t1 <- topTable(fit1,coef=1, number = Inf) t2 <- topTable(fit2,coef=1, number = Inf) rbind(head(t1, 3), tail(t1, 3)) # logFC AveExpr t P.Value adj.P.Val B # 92 -5.293932 5.810926 -8.200138 1.147084e-15 1.147084e-13 26.335702 # 81 -5.045682 5.949507 -7.815607 2.009706e-14 1.004853e-12 23.334600 # 37 -4.720906 6.182821 -7.312539 7.186627e-13 2.395542e-11 19.625964 # 27 -2.127055 6.854324 -3.294744 1.034742e-03 1.055859e-03 -1.141991 # 86 -1.938148 7.153142 -3.002133 2.776390e-03 2.804434e-03 -2.039869 # 75 -1.876490 6.516004 -2.906626 3.768951e-03 3.768951e-03 -2.314869 rbind(head(t2, 3), tail(t2, 3)) # logFC AveExpr t P.Value adj.P.Val B # 92 -4.518551 5.810926 -2.5022436 0.01253944 0.2367295 -4.587080 # 81 -4.500503 5.949507 -2.4922492 0.01289503 0.2367295 -4.587156 # 37 -4.111158 6.182821 -2.2766414 0.02307100 0.2367295 -4.588728 # 27 -1.496546 6.854324 -0.8287440 0.40749644 0.4158127 -4.595601 # 86 -1.341607 7.153142 -0.7429435 0.45773401 0.4623576 -4.595807 # 75 -1.171366 6.516004 -0.6486690 0.51673851 0.5167385 -4.596008 var(as.numeric(testexpr[, 6:10])) # [1] 12.38074 var(as.numeric(testexpr[, 6:7])) # [1] 0.8501378 var(as.numeric(testexpr[, 8:10])) # [1] 0.9640699As we can see the p-values returned from the first contrast are very small (large mean but small variance) but the p-values returned from the 2nd contrast are large (still large mean but very large variance). The variance from the "Other" group can be calculated from a mixture distribution ( pdf = .4 N(12, 1) + .6 N(5, 1), VarY = E(Y^2) - (EY)^2 where E(Y^2) = .4 (VarX1 + (EX1)^2) + .6 (VarX2 + (EX2)^2) = 73.6 and EY = .4 * 12 + .6 * 5 = 7.8; so VarY = 73.6 - 7.8^2 = 12.76). - Correct assumptions of using limma moderated t-test and the paper Should We Abandon the t-Test in the Analysis of Gene Expression Microarray Data: A Comparison of Variance Modeling Strategies.

- Evaluation: statistical power (figure 3, 4, 5), false-positive rate (table 2), execution time and ease of use (table 3)

- Limma presents several advantages

- RVM inflates the expected number of false-positives when sample size is small. On the other hand the, RVM is very close to Limma from either their formulas (p3 of the supporting info) or the Hierarchical clustering (figure 2) of two examples.

- Slides

- Use Limma to run ordinary T tests, Limma Moderated and Ordinary t-statistics

# where 'fit' is the output from lmFit() or contrasts.fit(). unmod.t <- fit$coefficients/fit$stdev.unscaled/fit$sigma pval <- 2*pt(-abs(unmod.t), fit$df.residual) # Following the above example t.test(testexpr[1, 1:5], testexpr[1, 6:10], var.equal = T) # Two Sample t-test # # data: testexpr[1, 1:5] and testexpr[1, 6:10] # t = -1.2404, df = 8, p-value = 0.25 # alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 # 95 percent confidence interval: # -7.987791 2.400082 # sample estimates: # mean of x mean of y # 4.577183 7.371037 fit2$coefficients[1] / (fit2$stdev.unscaled[1] * fit2$sigma[1]) # Ordinary t-statistic # [1] -1.240416 fit2$coefficients[1] / (fit2$stdev.unscaled[1] * sqrt(fit2$s2.post[1])) # moderated t-statistic # [1] -1.547156 topTable(fit2,coef=1, sort.by = "none")[1,] # logFC AveExpr t P.Value adj.P.Val B # 1 -2.793855 5.974110 -1.547156 0.1222210 0.2367295 -4.592992 # Square root of the pooled variance fit2$sigma[1] # [1] 3.561284 (((5-1)*var(testexpr[1, 1:5]) + (5-1)*var(testexpr[1, 6:10]))/(5+5-2)) %>% sqrt() # [1] 3.561284

- Comparison of ordinary T-statistic, RVM T-statistic and Limma/eBayes moderated T-statistic.

| Test statistic for gene g | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary T-test | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\overline{y}_{g1} - \overline{y}_{g2}}{S_g^{Pooled}/\sqrt{1/n_1 + 1/n_2}} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (S_g^{Pooled})^2 = \frac{(n_1-1)S_{g1}^2 + (n_2-1)S_{g2}^2}{n1+n2-2} }[/math] |

| RVM | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\overline{y}_{g1} - \overline{y}_{g2}}{S_g^{RVM}/\sqrt{1/n_1 + 1/n_2}} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (S_g^{RVM})^2 = \frac{(n_1+n_2-2)S_{g}^2 + 2*a*(a*b)^{-1}}{n1+n2-2+2*a} }[/math] |

| Limma | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\overline{y}_{g1} - \overline{y}_{g2}}{S_g^{Limma}/\sqrt{1/n_1 + 1/n_2}} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (S_g^{Limma})^2 = \frac{d_0 S_0^2 + d_g S_g^2}{d_0 + d_g} }[/math] |

- In Limma,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_g^2 }[/math] assumes an inverse Chi-square distribution with mean [math]\displaystyle{ S_0^2 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ d_0 }[/math] degrees of freedom

- [math]\displaystyle{ d_0 }[/math] (fit$df.prior) and [math]\displaystyle{ d_g }[/math] are, respectively, prior and residual/empirical degrees of freedom.

- [math]\displaystyle{ S_0^2 }[/math] (fit$s2.prior) is the prior distribution and [math]\displaystyle{ S_g^2 }[/math] is the pooled variance.

- [math]\displaystyle{ (S_g^{Limma})^2 }[/math] can be obtained from fit$s2.post.

- Empirical Bayes estimation of normal means, accounting for uncertainty in estimated standard errors Lu 2019

t.test() vs aov() vs sva::f.pvalue() vs genefilter::rowttests()

- t.test() & aov() & sva::f.pvalue() & AT function will be equivalent if we assume equal variances in groups (not the default in t.test)

- See examples in gist.

# Method 1:

tmp <- data.frame(groups=groups.gem,

x=combat_edata3["TDRD7", 29:40])

anova(aov(x ~ groups, data = tmp))

# Analysis of Variance Table

#

# Response: x

# Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

# groups 1 0.0659 0.06591 0.1522 0.7047

# Method 2:

t.test(combat_edata3["TDRD7", 29:40][groups.gem == "CR"],

combat_edata3["TDRD7", 29:40][groups.gem == "PD"])

# 0.7134

t.test(combat_edata3["TDRD7", 29:40][groups.gem == "CR"],

combat_edata3["TDRD7", 29:40][groups.gem == "PD"], var.equal = TRUE)

# 0.7047

# Method 3:

require(sva)

pheno <- data.frame(groups.gem = groups.gem)

mod = model.matrix(~as.factor(groups.gem), data = pheno)

mod0 = model.matrix(~1, data = pheno)

f.pvalue(combat_edata3[c("TDRD7", "COX7A2"), 29:40],

mod, mod0)

# TDRD7 COX7A2

# 0.7046624 0.2516682

# Method 4:

# load some functions from AT randomForest plugin

tmp2 <- Vat2(combat_edata3[c("TDRD7", "COX7A2"), 29:40],

ifelse(groups.gem == "CR", 0, 1),

grp=c(0,1), rvm = FALSE)

tmp2$tp

# TDRD7 COX7A2

# 0.7046624 0.2516682

# Method 5: https://stats.stackexchange.com/a/474335

# library(genefilter)

# Method 6:

# library(limma)

sapply + lm()

using lm() in R for a series of independent fits. Gene expression is on response part (Y). We have nG columns on Y. We'll fit a regression for each column of Y and the same X.

Treatment effect estimation

Permutation test

- When Your Permutation Test is Doomed to Fail

- Permutation P-values should never be zero: calculating exact P-values when permutations are randomly drawn Phipson & Smyth 2010

- getPvals() from singscore package. The null hypothesis is that the gene-set is not enriched in the sample. Question: it seems the permutation p-value is wrong. It should be calculated by using the tail values not by one-sided because the scores can be positive or negative.

# observed: 1 x nsamples # permuteResults: B x nsamples # pvals: 1 x nsamples pvals <- colSums(permuteResult > matrix(1, nrow = nrow(permuteResult), ncol = 1) %*% observed) / B # Consider B=1000, nsamples=5 # e.g. pvals = (0.996, 0.000, 0.999, 0.000, 0.530) pvals <- sapply(pvals, max, 1/B) # e.g. pvals = (0.996, 0.001, 0.999, 0.001, 0.530) range(permuteResult[,1]) # [1] -0.09813482 0.10853650 round(scoredf[,"TotalScore"], 3) # [1] -0.088 0.287 -0.099 0.271 -0.002 0.176 0.017 0.188 -0.062 -0.065 - In ArrayTools, LS score (= -sum (log p_j)) is always > 0. So the permutation p-value is calculated using one-sided.

- GSA package. Correct p-value in GSA (Gene set enrichment) permutation tests? Why it uses one-sided?

- Two-sided permutation test vs. two one-sided

- https://faculty.washington.edu/kenrice/sisg/SISG-08-06.pdf

- How about the fgsea package?

- Roughly estimate the number of permutations based on the desired FDR GSEA for RNA-seq analysis

ANOVA

- Practical Regression and Anova using R by Julian J. Faraway, 2002

- A simple ANOVA

- Repeated measures ANOVA in R Exercises

- Mixed models for ANOVA designs with one observation per unit of observation and cell of the design

- afex package, afex_plot(): Publication-Ready Plots for Factorial Designs

- Experiment designs for Agriculture

- ANOVA in R from statsandr.com

- Design and Analysis of Experiments by Montgomery

- https://cran.r-project.org/web/views/ExperimentalDesign.html

Partition of sum of squares

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partition_of_sums_of_squares

F-test in anova

How is the F-statistic computed in anova() when there are multiple models?

Common tests are linear models

https://lindeloev.github.io/tests-as-linear/

ANOVA Vs Multiple Comparisons

Post-hoc test

Determine which levels have significantly different means.

- http://jamesmarquezportfolio.com/one_way_anova_with_post_hocs_in_r.html

- pairwise.t.test() for one-way ANOVA

- Post-hoc Pairwise Comparisons of Two-way ANOVA using TukeyHSD().

- The "TukeyHSD()" function is then used to perform a post-hoc multiple comparisons test to compare the treatment means, taking into account the effect of the block variable.

summary(fm1 <- aov(breaks ~ wool + tension, data = warpbreaks)) # Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) # wool 1 451 450.7 3.339 0.07361 . # tension 2 2034 1017.1 7.537 0.00138 ** # Residuals 50 6748 135.0 TukeyHSD(fm1, "tension", ordered = TRUE) # Tukey multiple comparisons of means # 95% family-wise confidence level # factor levels have been ordered # # Fit: aov(formula = breaks ~ wool + tension, data = warpbreaks) # # $tension # diff lwr upr p adj # M-H 4.722222 -4.6311985 14.07564 0.4474210 # L-H 14.722222 5.3688015 24.07564 0.0011218 # L-M 10.000000 0.6465793 19.35342 0.0336262 tapply(warpbreaks$breaks, warpbreaks$tension, mean) # L M H # 36.38889 26.38889 21.66667 26.38889 - 21.66667 # [1] 4.72222 # M-H 36.38889 - 21.66667 # [1] 14.72222 # L-H 36.38889 - 26.38889 # [1] 10 # L-M plot(TukeyHSD(fm1, "tension"))

- post-hoc tests: pairwise.t.test versus TukeyHSD test

- How to Perform Dunnett’s Test in R

- How to do Pairwise Comparisons in R?

- [https://www.statology.org/tukey-vs-bonferroni-vs-scheffe/

TukeyHSD (Honestly Significant Difference), diagnostic checking

https://datascienceplus.com/one-way-anova-in-r/, Tukey HSD for Post-Hoc Analysis (detailed explanation including the type 1 error problem in multiple testings)

- TukeyHSD for the pairwise tests

- You can’t just perform a series of t tests, because that would greatly increase your likelihood of a Type I error.

- compute something analogous to a t score for each pair of means, but you don’t compare it to the Student’s t distribution. Instead, you use a new distribution called the studentized range (from Wikipedia) or q distribution.

- Suppose that we take a sample of size n from each of k populations with the same normal distribution N(μ, σ) and suppose that [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{y} }[/math]min is the smallest of these sample means and [math]\displaystyle{ \bar{y} }[/math]max is the largest of these sample means, and suppose S2 is the pooled sample variance from these samples. Then the following random variable has a Studentized range distribution: [math]\displaystyle{ q = \frac{\overline{y}_{\max} - \overline{y}_{\min}}{S/\sqrt{n}} }[/math]

- One-Way ANOVA Test in R from sthda.com.

res.aov <- aov(weight ~ group, data = PlantGrowth) summary(res.aov) # Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) # group 2 3.766 1.8832 4.846 0.0159 * # Residuals 27 10.492 0.3886 TukeyHSD(res.aov) # Tukey multiple comparisons of means # 95% family-wise confidence level # # Fit: aov(formula = weight ~ group, data = PlantGrowth) # # $group # diff lwr upr p adj # trt1-ctrl -0.371 -1.0622161 0.3202161 0.3908711 # trt2-ctrl 0.494 -0.1972161 1.1852161 0.1979960 # trt2-trt1 0.865 0.1737839 1.5562161 0.0120064 # Extra: # Check your data my_data <- PlantGrowth levels(my_data$group) set.seed(1234) dplyr::sample_n(my_data, 10) # compute the summary statistics by group library(dplyr) group_by(my_data, group) %>% summarise( count = n(), mean = mean(weight, na.rm = TRUE), sd = sd(weight, na.rm = TRUE) ) - Or we can use Benjamini-Hochberg method for p-value adjustment in pairwise comparisons

library(multcomp) pairwise.t.test(my_data$weight, my_data$group, p.adjust.method = "BH") # ctrl trt1 # trt1 0.194 - # trt2 0.132 0.013 # # P value adjustment method: BH

- Shapiro-Wilk test for normality

# Extract the residuals aov_residuals <- residuals(object = res.aov ) # Run Shapiro-Wilk test shapiro.test(x = aov_residuals )

- Bartlett test and Levene test for the homogeneity of variances across the groups

Repeated measure

- How to do Repeated Measures ANOVAs in R

- Cross-over Repeated Measure Designs

- Cross-over study design with a major constraint

- Repeated Measures of ANOVA in R Complete Tutorial

Combining insignificant factor levels

COMBINING AUTOMATICALLY FACTOR LEVELS IN R

Omnibus tests

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omnibus_test

- Understanding the definition of omnibus tests Tests are refereed to as omnibus if after rejecting the null hypothesis you do not know where the differences assessed by the statistical test are. In the case of F tests they are omnibus when there is more than one df in the numerator (3 or more groups) it is omnibus.

One-way ANOVA

https://www.mathstat.dal.ca/~stat2080/Fall14/Lecturenotes/anova1.pdf

Randomized block design

- What is a randomized block design?

- In a randomized block design, the subjects are first divided into blocks based on their similarities, and then they are randomly assigned to the treatment groups within each block.

- How to interpret the result from a randomized block design?

- If the results are statistically significant, it means that there is a significant difference between the treatment groups in terms of the response variable. This indicates that the treatment had an effect on the response variable, and that this effect is not likely due to chance alone.

- How to incorporate the block variable in the interpretation?

- In a randomized block design, the block variable is a characteristic that is used to group the subjects or experimental units into blocks. The goal of using a block variable is to control for the effects of this characteristic, so that the effects of the experimental variables can be more accurately measured.

- To incorporate the block variable into the interpretation of the results, you will need to consider whether the block variable had an effect on the response variable.

- If the block variable had a significant effect on the response variable, it means that the results may be confounded by the block variable. In this case, it may be necessary to take the block variable into account when interpreting the results. For example, you might need to consider whether the treatment effects are different for different blocks, or whether the block variable is interacting with the treatment in some way.

- What does that mean the result is confounded by the variable?

- If the results of an experiment are confounded by a variable, it means that the variable is influencing the results in some way and making it difficult to interpret the effects of the experimental treatment. This can occur when the variable is correlated with both the treatment and the response variable, and it can lead to incorrect conclusions about the relationship between the treatment and the response.

- For example, consider an experiment in which the treatment is a drug that is being tested for its ability to lower blood pressure. If the subjects are divided into blocks based on their age, and the results show that the drug is more effective in younger subjects than in older subjects, this could be because the drug is more effective in younger subjects, or it could be because blood pressure tends to be higher in older subjects and the effect of the drug is being masked. In this case, the results would be confounded by age, and it would be difficult to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the drug without taking age into account.

- To avoid confounding, it is important to carefully control for any variables that could potentially influence the results of the experiment. This may involve stratifying the sample, using a matching or blocking design, or controlling for the variable in the statistical analysis. By controlling for confounding variables, you can more accurately interpret the results of the experiment and draw valid conclusions about the relationship between the treatment and the response.

- What are the advantages of a randomized block design?

- Control for extraneous variables: By grouping subjects into blocks based on a similar characteristic, a randomized block design can help to control for the effects of this characteristic on the response variable. This makes it easier to accurately measure the effects of the experimental variables.

- Increased precision: Randomizing the subjects within each block helps to reduce the variance among the treatment groups. This increase the power of the statistical analysis and makes it more likely to detect true differences between the treatment groups.

- Reduced sample size: Randomized block designs typically require a smaller sample size than completely randomized designs to achieve the same level of precision. This makes it more cost-effective and logistically easier to conduct the research

- Identify the characteristics that affect the response: The block design can help to identify the characteristics of subjects or experimental units that affect the response variable. This can help to identify important factors that should be controlled for in future experiments or can be used to improve the understanding of the phenomena being studied.

- Multiple comparison: with multiple blocks allows to perform multiple comparison of the treatment groups, which can help to identify specific variables or groups that are contributing to the overall results and to understand the mechanism of the effect.

- What are the disadvantages of randomized block design

- Complexity

- Difficulty in identifying blocks

- Increases experimental control

- Difficulty in interpretation: When multiple blocks are used it can be difficult to interpret the results of the experiment and it's crucial to have sufficient sample size within each block to detect the effects of the experimental variable.

- Does the power of the test change with the number of levels in the block variable in randomized block design analysis?

- The analysis for a randomized block design does not change with the number of levels in the block variable, but the number of levels in the block variable does affect the power of the analysis. As the number of levels in the block variable increases, the power of the test to detect differences among treatments also increases. However, increasing the number of levels in the block variable also increases the number of blocks required, which can make the study more complex and costly to conduct.

- How does the block variable affect the interpretation of the significant of the main effect in a randomized block design?

- In a randomized block design, the block variable is used to control for sources of variation that are not of interest in the study, but that may affect the response variable. By blocking, we are trying to make sure that any differences in the response variable among the treatments are due to the treatment and not due to other sources of variation.

- The main effect of the block variable represents the difference in the response variable among the blocks, regardless of the treatment. If the main effect of the block variable is significant, it means that there are systematic differences in the response variable among the blocks, and that the blocks are not exchangeable. This can affect the interpretation of the main effect of the treatment variable.

- When the main effect of the block variable is significant, it means that the blocks are not homogeneous and that the treatment effect may be different among the blocks. In this case, we cannot conclude that the treatment effect is the same across all blocks. Therefore, it's important to examine the interaction between the block and treatment variables, which tells us whether the treatment effect is the same across all blocks. If the interaction is not significant, it means that the treatment effect is the same across all blocks, and we can conclude that the treatment has a consistent effect on the response variable. However, if the interaction is significant, it means that the treatment effect varies among the blocks, and we cannot conclude that the treatment has a consistent effect on the response variable.

- In summary, when the main effect of the block variable is significant, it means that the blocks are not homogeneous, and it may affect the interpretation of the main effect of the treatment variable. The effect of treatment may vary across the blocks and it's important to examine the interaction between the block and treatment variables to understand whether the treatment effect is consistent across all blocks.

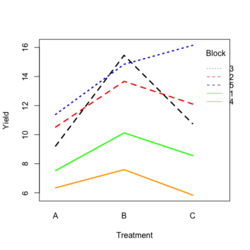

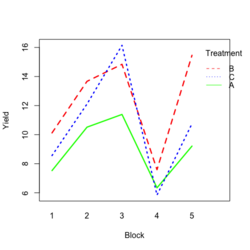

- Visualize the data. Both treatment and block variables are significant.

- Examples

- Random data

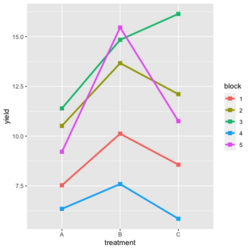

library(ggplot2) #create a dataframe set.seed(1234) block <- factor(rep(1:5, each=6)) treatment <- rep(c("A","B","C"),5) yield <- rnorm(30, mean = 10, sd = 2) data <- data.frame(block, treatment, yield) summary(aov(yield ~ treatment + block, data = data)) # Create the box plot # By using the group argument with the interaction(block, treatment) function, # we are grouping the data by both the block and treatment variables, which means that # we will have a separate box plot for each unique combination of block and treatment. ggplot(data, aes(x = treatment, y = yield)) + geom_boxplot(aes(group = interaction(block, treatment), color = block)) + ggtitle("Main Effect of Treatment") + xlab("Treatment") + ylab("Yield")- Create a randomized block design data where the block variable is not significant but the treatment variable is significant:

set.seed(1234) block <- factor(rep(1:5, each=6)) treatment <- rep(c("A","B","C"),5) yield <- rnorm(30, mean = 10, sd = 2) + ifelse(treatment == "B", 2,0) data <- data.frame(block, treatment, yield) summary(fm1 <- aov(yield ~ treatment + block, data = data)) # Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) # treatment 2 69.92 34.96 13.163 0.000155 *** # block 4 11.94 2.99 1.124 0.369624 # Residuals 23 61.09 2.66 TukeyHSD(fm1, "treatment", order = T) # order = T: A logical value indicating if the levels of the factor should be ordered # according to increasing average in the sample before taking differences. If ordered # is true then the calculated differences in the means will all be positive. # # Tukey multiple comparisons of means # 95% family-wise confidence level # factor levels have been ordered # $treatment # diff lwr upr p adj # C-A 1.851551 0.02630618 3.676796 0.0463529 # B-A 3.739487 1.91424233 5.564732 0.0000968 # B-C 1.887936 0.06269108 3.713181 0.0417048 TukeyHSD(fm1, "treatment") # diff lwr upr p adj # B-A 3.739487 1.91424233 5.56473246 0.0000968 # C-A 1.851551 0.02630618 3.67679631 0.0463529 # C-B -1.887936 -3.71318121 -0.06269108 0.0417048- An example where both the block and treatment var are significant

summary(fm1 <- aov(yield ~ treatment + block, data = data)) # Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) # treatment 2 92.09 46.05 9.555 0.000954 *** # block 4 140.45 35.11 7.286 0.000607 *** # Residuals 23 110.84 4.82

gl(): Generate Factor Levels

Two-way ANOVA

- Interpreting Interactions when Main Effects are Not Significant

- Actually, you can interpret some main effects in the presence of an interaction

- Confusion about Deseq2 wording in the vignette (additive model with main effects only vs interaction)

- Why and When to Include Interactions in a Regression Model

- they have large main effects

- the effect of one changes for various subgroups of the other

- the interaction has been proven in previous studies

- you want to explore new hypotheses

- How to interpret main effects when the interaction effect is not significant?

- When Main Effects are Not Significant, But the Interaction Is. A cross-over interaction.

- Main effects are not significant anymore after adding interaction terms in my linear regression. Frank Harrell answered.

- Can the interaction term of two insignificant coefficients be significant?

- Why does the main effect become not significant when I add an interaction term in a regression model? The interaction effect is more influential in explaining differences in the outcome variable than either the "main effect". moderator

- Including an Interaction term leads to insignificant direct effects. The "main effects" no longer carry the same meaning when an interaction term is included in the model, so their coefficients have no necessary relationship to the coefficients seen by the variables of the same name in a no-interaction model.

- How to Create an Interaction Plot in R? stats::interaction.plot()

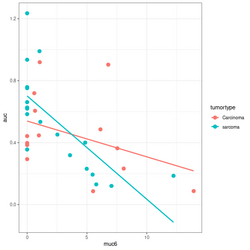

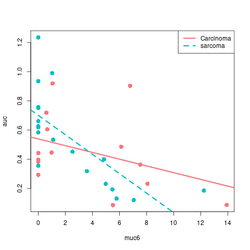

An example

devtools::source_gist("https://gist.github.com/arraytools/88449e3c92c752eb7a66ee0189b09606")

dim(df) # [1] 33 3

df[1:2, ]

# muc6 tumortype auc

# V1 0.6599192 Carcinoma 0.6056

# V2 12.2342844 sarcoma 0.1858

summary(lm(auc~muc6, data=df))

# Coefficients:

# Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

# (Intercept) 0.63065 0.05388 11.706 6.56e-13 ***

# muc6 -0.04367 0.01119 -3.903 0.000478 ***

# Residual standard error: 0.2407 on 31 degrees of freedom

# Multiple R-squared: 0.3295, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3079

# F-statistic: 15.23 on 1 and 31 DF, p-value: 0.000478

summary(lm(auc~., data=df))

# Coefficients:

# Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

# (Intercept) 0.61262 0.07764 7.891 8.32e-09 ***

# muc6 -0.04312 0.01148 -3.758 0.000739 ***

# tumortypesarcoma 0.02846 0.08697 0.327 0.745791

# Residual standard error: 0.2443 on 30 degrees of freedom

# Multiple R-squared: 0.3319, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2873

# F-statistic: 7.451 on 2 and 30 DF, p-value: 0.00236

summary(lm(auc~muc6*tumortype, data=df))

# Coefficients:

# Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

# (Intercept) 0.53938 0.08281 6.514 3.93e-07 ***

# muc6 -0.02312 0.01490 -1.552 0.1316

# tumortypesarcoma 0.16194 0.10690 1.515 0.1406

# muc6:tumortypesarcoma -0.04356 0.02198 -1.982 0.0571 .

# Residual standard error: 0.2332 on 29 degrees of freedom

# Multiple R-squared: 0.4116, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3507

# F-statistic: 6.761 on 3 and 29 DF, p-value: 0.001352

library(ggplot2); library(magrittr)

df %>% ggplot(aes(muc6, auc, col=tumortype)) +

geom_point(size=3) +

geom_smooth(method="lm",se = FALSE)

# Base R plot version

col2 <- c("#F8767D", "#00BFC4") # see my ggplot2 page

col <- col2[as.integer(factor(df$tumortype))]

f$tumortype[1:5]

# [1] "Carcinoma" "sarcoma" "Carcinoma" "Carcinoma" "sarcoma"

as.integer(factor(df$tumortype))[1:5]

# [1] 1 2 1 1 2

plot(df$muc6, df$auc, col = col, xlab="muc6", ylab="auc", pch=16, cex=1.5)

abline(a = coefs[1], b=coefs[2], col = col2[1], lwd=3)

abline(a = coefs[1] + coefs[3], b = coefs[2] + coefs[4], lty=2, col = col[2], lwd=3)

legend("topright", c("Carcinoma", "sarcoma"), col = col2, lty=1:2, lwd=3)

Type I, II and III Sums of Squares

- Type I, II and III Sums of Squares – the explanation

- type I (sequential): SS(A) for factor A. SS(B | A) for factor B. SS(AB | B, A) for interaction AB. If the data is unbalanced, you will get a different result of using anova(lm(y ~ A * B, data=search)) & anova(lm(y ~ B * A, data=search)). This is default in R.

- type II (ADDED AFTER OTHER MAIN EFFECTS): SS(A | B) for factor A. SS(B | A) for factor B. R's anova().

- type III (ADDED LAST): SS(A | B, AB) for factor A. SS(B | A, AB) for factor B. This is the default in SAS. In R, car:::Anova(, type="III").

- Everything You Always Wanted to Know About ANOVA

- It seems the order does not make a difference in linear regression or Cox regression.

Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kruskal%E2%80%93Wallis_one-way_analysis_of_variance

- How to perform the Kruskal-Wallis test in R?

- Kruskal Wallis test in R-One-way ANOVA Alternative

Multilevel, Simpson paradox

Multilevel Correlations: A New Method for Common Problems. Simpson paradox.

ANCOVA

MANOVA

- MANOVA(Multivariate Analysis of Variance) using R

- MANOVA in R – How To Implement and Interpret One-Way MANOVA